A bowl of gumbo can tell you exactly where you are in Louisiana. Ask any cook about their recipe, and you’ll get a list of ingredients and a story that reveals whether it’s Creole or Cajun heritage simmering in the pot. Gumbo, like many South Louisiana dishes, is more than a meal; it’s identity, memory, and history, all stirred together.

Tomatoes and a lighter roux are telltale signs of a Creole gumbo, most often found in New Orleans, a port city shaped by French, Spanish, African, Caribbean, and Italian influences. Okra usually makes an appearance, too, along with more variations, thanks to an abundance of fresh vegetables.

Head into Cajun country, and the gumbo tells a different story. Here, the roux is dark, deep, and smoky, built with chicken, sausage, or sometimes wild game, and sometimes served with a scoop of potato salad right in the bowl.

I’m a LeBlanc, a native Louisianian and Cajun descendant who grew up on chicken-and-andouille sausage gumbo, an unwritten family recipe passed down the old-fashioned way by watching and doing. My mom taught me how to make a roux, how to stir the flour and oil just enough so it doesn’t stick or burn in the bottom of the cast-iron pot. She taught me how to sauté the trinity, that essential trio of gumbo ingredients, celery, bell pepper, and onion, until it turned translucent and fragrant, just shy of golden, without letting the edges brown. That cast-iron pot and the old wooden spoon I learned to cook with are family heirlooms I inherited, passed down, and seasoned with my family’s stories.

Gumbo is one of the many nuances in Cajun and Creole culture that are often blurred, simplified, and commodified, missing the deeper story of two distinct cultures. The words “Creole” and “Cajun” usually appear interchangeably on menus, in travel brochures, and even in everyday conversation. Growing up in South Louisiana, I often heard those labels used casually, sometimes simplified or romanticized, but I’ve come to see that there’s a much richer story beneath the surface, one that speaks to the depth and diversity of who we really are.

To really understand the difference between Cajun and Creole culture, how it shows up in our food, music, and traditions, I went straight to the source, first to New Orleans, the cradle of Creole culture, then over to Acadiana in southwestern Louisiana, known as Cajun country.

My journey is about honoring generational knowledge, lived experiences, and the people who keep these cultures vibrant and alive, rather than about culinary and cultural correction.

Familiar tropes often describe the Crescent City, Bourbon Street revelry, Mardi Gras parades, rattling streetcars, and menus boasting “Cajun food.” But while the world may call New Orleans Cajun, its roots are unmistakably Creole. Creole culture was born in colonial Louisiana, shaped by the descendants of Europeans and Africans who built a rich, layered identity. As a port city, New Orleans became the heart of this cultural mix. In the early 1800s, after Louisiana became a U.S. territory, “Creole” came to mean anyone born in the New World who spoke French, regardless of their roots.

To truly understand Creole culture, I rolled up my sleeves and headed to the kitchen for a hands-on cooking class at Deelightful Roux School of Cooking in Central City, New Orleans. Chef Dee Lavigne owns and operates the cooking school at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum, a nonprofit museum that explores the culinary history of the American South.

Before I tied on my apron, I took a walk through the museum for a crash course in Louisiana’s legendary culinary legacy built by barrier-breaking chefs and restaurateurs. There’s Leah Chase, the Queen of Creole Cuisine, who ran Dooky Chase’s Restaurant with her husband, Edgar “Dooky” Chase Jr. It was the first fine-dining establishment for African Americans in New Orleans and hosted Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Thurgood Marshall.

Then there’s Owen Brennan, who opened Brennan’s Restaurant in 1946 to showcase French and Creole cuisine and helped invent one of the city’s most iconic desserts, Bananas Foster. Ella Brennan, a force in the family-run restaurant dynasty, took the reins at Commander’s Palace and launched the careers of celebrity chefs Paul Prudhomme and Emeril Lagasse. The list of culinary greats continues to grow and gain global recognition, with the Michelin Guide’s 2024 recognition of Louisiana’s food scene as part of its inaugural selection for the American South. Several Louisiana restaurants received stars, including Emeril’s in New Orleans, Saint‑Germain, and Zasu, and more than 30 received Michelin recommendations.

Chef Dee, a New Orleans native, is following in the trailblazing footsteps of Chef Lena Richard, a pioneering African American chef, author, and TV personality born in 1892, who shattered racial and gender barriers. Chef Dee is only the second African American woman to own and operate a cooking school in New Orleans, carrying forward that legacy.

Our lesson kicks off at one of several prep stations where Chef Dee shows me how to slice and devein shrimp for a classic Creole gumbo with tomatoes. Also on the menu: smothered okra and tomatoes, and New Orleans’ famous Bananas Foster.

As I sauté the trinity of onions, celery, and bell pepper, Chef Dee looks over and smiles. “Onions are the diva of vegetables,” she jokes. “They take over the show, scream the loudest, and will make you cry.” Throughout the class, she weaves in stories, food lore, and cooking wisdom. I learn that jambalaya is traditionally made from leftovers, which is why you’ll often find it served on weekends. And rice? It doesn’t always need boiling; it can cook in the steam from tomatoes, absorbing all that flavor.

What’s poured into your glass also reflects Creole culture, especially in cocktails like the Sazerac, which was officially named Louisiana’s state cocktail in 2008. Made with rye whiskey and Peychaud’s bitters, the Sazerac dates back to the 19th century, though its origins go much further back.

At the Sazerac House in the New Orleans Central Business District, I joined a cocktail class led by drinks historian Elizabeth Pearce, who taught us how to make cocktails that embody the city’s culture. We stir simple syrup, bitters, and Sazerac rye whisky with ice in a mixing glass. In a separate chilled rocks glass, swirl in a splash of absinthe to coat the inside, then pour out the excess. Strain the whiskey mixture into the glass and garnish with a twist of lemon peel. We drink it neat, without ice, to appreciate its smooth, aromatic, and spirit-forward flavor.

Like so much of Louisiana culture, the Sazerac began as a practical solution. In the early 1800s, Creole apothecary Antoine Amédée Peychaud, who fled the Haitian Revolution and settled in New Orleans around 1795, created a proprietary bitters to aid digestion. He served it in his Royal Street apothecary, mixed with French brandy and a little sugar, poured into small egg-shaped cups called coquetiers. Many historians believe those cups filled with his medicinal mixture may have even given us the word “cocktail.”

The Sazerac Coffee House began serving the now-famous drink, and it quickly caught on with locals. When a phylloxera outbreak devastated French vineyards later in the 19th century, cognac became scarce. Bartenders in New Orleans, including Thomas H. Handy, then-owner of the Sazerac House, adapted by swapping the brandy for American rye whiskey, while keeping Peychaud’s Bitters at the heart of the drink.

After the cocktail class, I explored the Sazerac House museum and its distillery room. Sazerac rye whiskey is distilled in New Orleans, though it’s aged in Kentucky, where the climate is cooler and more stable. Peychaud’s Bitters are still crafted in New Orleans and remain a hallmark of Louisiana’s culinary heritage and cocktail tradition.

New Orleans is a city with a sound all its own, best known as the birthplace of Jazz, a music of improvisation that fuses African spirituals and Creole musicians playing brass instruments. The genre originated in places like Congo Square, where enslaved Africans and free people of color gathered on Sundays to dance to African rhythms and spirituals. Brass bands, funeral parades, and the riverboat gigs folded in the Blues, giving rise to legendary performers, many of whom got their start at The Dew Drop Inn.

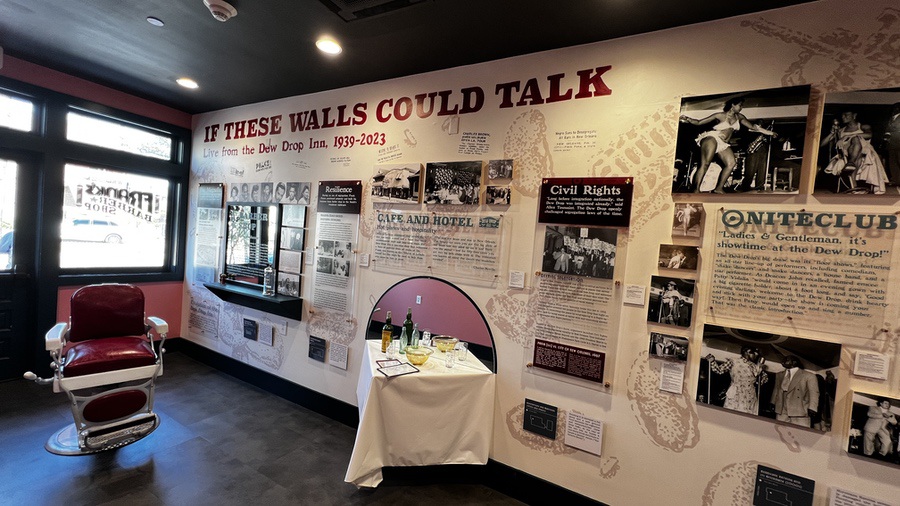

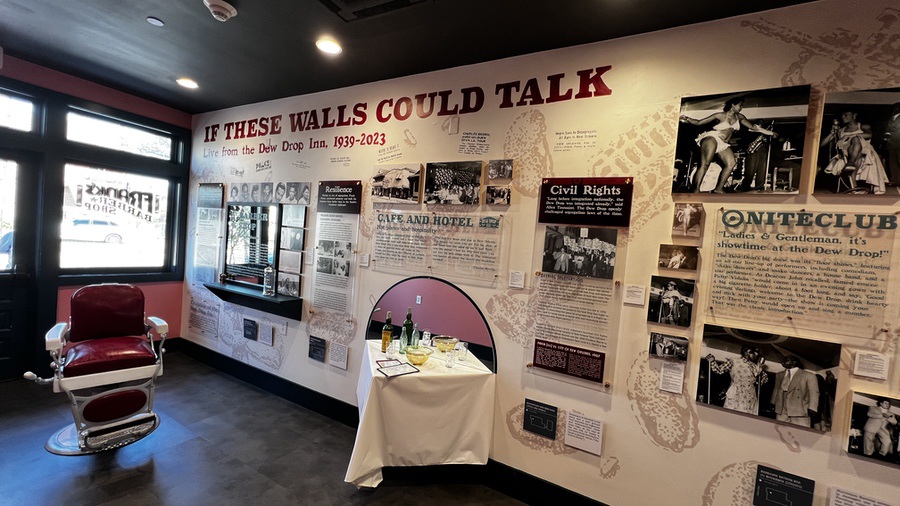

The Dew Drop Inn, a star-maker for Black musicians when it opened in 1939 and became a popular stop on the Chitlin Circuit, an infrastructure of venues that catered to Black musicians. Frank Painia owned and operated the establishment, which included a barber shop, restaurant, nightclub, and hotel. The Dew Drop Inn was listed in the Green Book, a travel guide that helped African Americans navigate segregation during the Jim Crow era and provided a venue where Black musicians could play to a mixed crowd.

“There was a time when white people would get arrested, along with other patrons, anybody who was in here, because selling drinks during segregation to a mixed crowd was illegal. There was a law that specifically stated there needed to be a ceiling-to-floor partition that separated the two groups if you were going to be selling alcohol,” says Curtis Doucette, a New Orleans developer and current owner of The Dew Drop Inn.

Today, the intimate live music venue and a 17-room boutique hotel pay tribute to the legends who helped shape American rhythm and blues. The hotel rooms pay homage to musicians with pictures, memorabilia, and bios that chronicle their time at the Dew Drop Inn. The Frank Painia room, known as the VIP Groove Room, features a living room that overlooks the stage. “Every room in the house is a museum, dedicated to someone with a close connection to the Dewdrop Inn,” Curtis says.

The original barbershop still stands and serves as a museum, with displays and photos that depict the Dew Drop Inn’s role in music and Civil Rights history. Just about any famous Black musician has played on this stage, including James Brown, Alan Toussaint, Ray Charles, Little Richard, Etta James, and Aretha Franklin. “Little Richard first improvised Tutti Frutti, which became his breakout hit, right here at the Dewdrop Inn,” Curtis says. Other famous names that took the stage include James Brown, Tina Turner, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, and Irma Thomas. Frank Painia’s grandson, Kenneth Jackson, held on to the building after The Dew Drop Inn closed down in 1970, hoping to restore it as a music venue. In 2023, The Dew Drop Inn reopened, promoting New Orleans’ next generation of artists while honoring its musical legacy.

I attended a Saturday brunch, Legends of the Dew Drop: Road to Rock and Roll, a musical journey tracing the evolution of Rhythm & Blues and Rock & Roll on the very New Orleans stage that once launched these sounds onto the world stage. Actress Tanyell Quian, who appeared in the TV show Queen Sugar, hosts the mix of storytelling and hit performances from icons like Ray Charles, Little Richard, and Dave Bartholomew. The music is irresistible, which is why this is a dine-and-dance brunch, where the dance floor welcomes everyone, just as it has for generations.

As the Dew Drop Inn reclaims its place in New Orleans music history, just across town, in the Warehouse Arts District, venues like The Peacock Room are offering a more contemporary stage. The live music bar and restaurant at Hotel Fontenot pays homage to New Orleans Jazz with regular performances by local artists, including Robin Barnes, who has performed with Pat Casey and Da Lovebirds. Blue velvet couches and chairs encircle the stage in a cozy, living room-style layout, all wrapped in a lush, peacock-plumed ambiance. On the night I attended, Robin sang songs from her new album, Louisiana Love. “From grandmother to daughter, eight generations of Louisiana live on these songs,” Robin explains. “Music is a common thread, celebrating who we are, remembering what we’ve lost, and ensuring our spirit carries forward.”

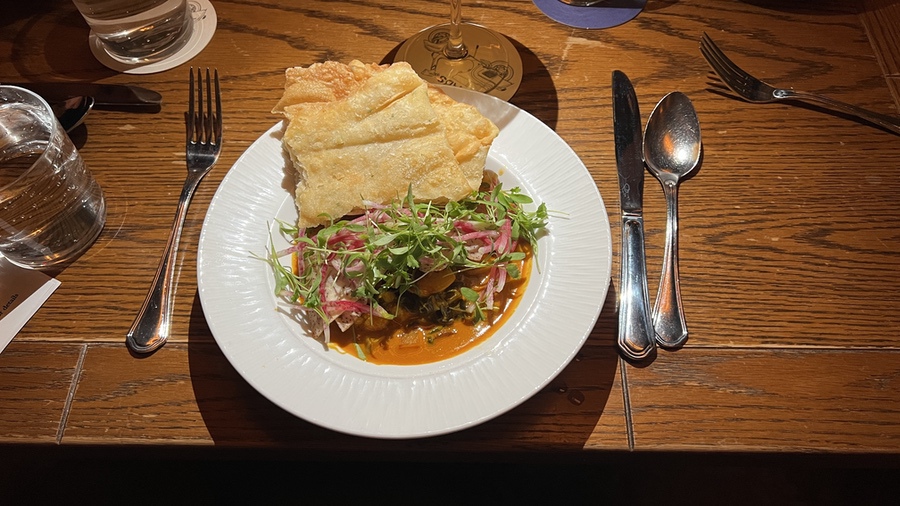

The Peacock Room was a few blocks from my hotel, The Old No. 77 Hotel & Chandlery, where I stayed to connect with local art and history. The restored building began its life in 1854 as a coffee warehouse and later became a chandlery that sold goods used for sailing voyages. The Old No. 77 Hotel & Chandlery takes its name from this original address. I dined at Chef Nina Compton’s Compère Lapin (French for “brother rabbit”) inside the hotel, a Michelin-recommended restaurant that fuses Caribbean and Creole cuisines and cultures. Chef Compton is from St. Lucia, and her cooking draws from family traditions shaped by heritage ingredients rooted in African, Indigenous, and early colonial influences. I ordered the restaurant’s signature Curried Goat with Sweet Potato Gnocchi, the restaurant’s most popular dish since opening in 2015.

Compère Lapin echoes the hotel’s rustic vibe with exposed brick walls, mosaic tiled flooring, and dim lighting punctuated by a sleek wine wall of glass display cases. The entire building is an art gallery displaying the works of local artists, painters, sculptors, craftspeople, and jewelry designers. Each piece displays a scannable code to learn more about its creative origins. Art also hangs on the exposed brick walls of each hotel room, outfitted with the building’s original wood-plank floors, midcentury modern decor, and vintage elements, including a dial radio. The lobby embodies the building’s patina with the weathered owner’s original painted brick sign, worn leather couches, and a vintage cigarette vending machine repurposed as an Art-O-Mat that sells small, affordable artwork and warns that the contents are not toys.

Throughout Louisiana, heritages blend, intersect, and echo across a shared cultural landscape, especially in cities like Lafayette, where diverse traditions meet at the crossroads of culture. Lafayette is located in south-central Louisiana, in the heart of Acadiana, where Cajun culture blends with Creole influences. “Food, music, and rituals move across cultural boundaries, adapt, and generate new forms to showcase our region not as a set of parallel traditions, but as a living, breathing ecosystem of culture,” explains Jesse Guidry, Vice President of Lafayette Travel.

Acadiana is known as Cajun Country, the place where Acadian people immigrated from 1755 to 1764, when the British forced them from present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Many settled along the bayous of South Louisiana and became known as Cajuns, small farmers and skilled craftspeople who lived off the land. Their distinctive French dialect and once-marginalized way of life are now admired and celebrated around the world.

Throughout Acadiana, you find regular gatherings of Cajun French speakers in cafes, chatting in their ancestral tongue. On a Thursday morning, and through the window of Dwyer’s Café in downtown Lafayette, I watch a group of patrons in animated French conversation, hands gesticulating in between sips of coffee. Dwyer’s is one of the regular gathering spots for a French Table in Acadiana. In this informal tradition, people come together to speak and share Louisiana French, helping keep the language and culture alive in the community.

I don’t speak Cajun French. I learned French from textbooks and classroom teachers, so my pronunciation differs from the melodic cadence of my Cajun-speaking great-grandparents, great-aunts, and uncles. By the time my father’s generation came along, Cajun French became silent in our family tree. Louisiana Lawmakers in 1921 banned French from being spoken in classrooms, changing and shaming the lives of thousands of French-speaking families. Cajun French slipped through the cracks of my father’s generation, part of a larger story of cultural loss across south Louisiana that the state is trying to correct through funding and support of CODOFIL, the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana. It’s a state agency founded in 1968 to promote and support the French language and Francophone cultures in Louisiana.

Inside Dwyer’s, I feel a connection to my heritage and an appreciation for culture bearers who keep Cajun French alive. I’m here for the fluffy biscuits, the buttered grits, the bottomless coffee, and the bond of shared roots. Just about everyone in Lafayette already knows this corner café. Folks have been gathering at Dwyer’s Café since 1927 for all-day breakfast, strong coffee, and daily specials of Louisiana’s bounty, including shrimp stew, fried catfish, shrimp étouffée, shrimp-and-crab casserole, okra, and black-eyed peas. Inside, the walls read like a family scrapbook: photographs of the three generations who’ve owned and run the café, flanked by framed accolades, yellowing newspaper clippings, glossy magazine features, and my personal favorite, a giant silver spoon proclaiming Dwyer’s “The best place to take Paw Paw to lunch downtown.”

“We live in a region of ongoing conversation where cuisine, music, stories, and ritual continue to evolve through exchange, adaptation, and creative resilience,” Jesse says. That cultural conversation Jesse describes manifests in a joie de vivre that brings people together to eat, drink, dance, and celebrate. Louisiana hosts more than 400 festivals a year, so no matter when you visit, there’s likely one happening nearby.

A typical Saturday morning is reason enough to celebrate at Buck & Johnny’s World Famous Zydeco Breakfast in Breaux Bridge. Crowds line up early on Saturday mornings, where the first-come, first-served, no-reservation policy rewards those in line the earliest outside the old Domingue’s Motors building. Patrons pay the 10-dollar cover charge and can opt for the menu’s 20-dollar endless mimosas and nonstop dancing. On the Saturday morning I attended, CJ Vedell and the Zydeco Grapplers were performing from 8:30 am to 11:30 am.

The waitress fills my coffee mug that says “Allons Danser!” French for “Let’s Dance,” a hint that this won’t be a spectator breakfast. I ordered up Beignets and Eggs Savoy, two poached eggs plus a biscuit topped with crab, portabella brie, and a Cajun crabcake. I’m wearing tennis shoes, rather than cowboy boots, a dead giveaway that this was my first Zydeco breakfast, and I observe to learn the unspoken rules. Those who come to dance, not dine, sit in a line of chairs along the back wall, facing the dancefloor. CJ Vedell begins strumming his rubboard as another musician plays the accordion, cueing folks out on the dance floor. Patrons fan out and pick their dance partners from those seated at breakfast tables or congregating around the dance floor.

I head upstairs for an overhead view of the dance floor and watch a grandmother take the lead with her infant grandson as the dance floor fills up with people of all ages, two-stepping to the staccato beats. I vowed to return in appropriate footwear and, after a dance lesson, to glide across the floor like the locals to the joyful music.

Zydeco music blends influences from Creole, Cajun, blues, and R&B. Musicians play the rubboard (or washboard) with spoons, and the keyboard accordion leads the two-step beat. Cajun music gets its signature sound from the button accordion alongside the fiddle, guitar, and the Cajun triangle, known locally as the t’fer or little iron.

Brandy Aube is a Cajun musician and self-taught metal fabricator, welder, and artisan who hand-forges the t’fer in her shop Studio Aubé Metalwork in Breaux Bridge. I watched her creative process, heating the iron, hand-hammering, and bending the glowing metal into melodic form using a custom mold of her own design. I was impressed by the craftsmanship, so I purchased one for myself as a keepsake and heirloom that connects to my Cajun roots.

I met Brandy at Maison Madeleine’s Secret Supper, a reservation-only dinner at an 1840s Creole cottage listed on the National Register of Historic Places on Lake Martin in Breaux Bridge.

Owners Madeleine Cenac and her husband, Walt Adams, restored the home into a bed-and-breakfast known for its southern hospitality and heritage-based dining experiences. The couple’s Secret Suppers sell out fast and feature Cajun & Creole Grammy-winning musicians and dishes cooked by James Beard Award-nominated chefs.

Another creole cottage on the property hosts the culinary event, inviting you to linger on the front porch before dinner, listening to live Cajun music while sipping natural wine served by Wild Child wines and sampling hors d’ouveres of shrimp and grits and farm-raised oysters shucked on demand by Barataria Beauties Oyster Company in Grand Isle. On the night I dined, musicians, Yvette Landry and Beau Thomas, performed ancestral tunes of Cajun, Creole, Juré, and Swamp Pop, sprinkled with stories and explanations of the instruments, including the fiddle, often mistaken for a violin. Beau jokes that the difference between a fiddle and a violin is that “you don’t spill beer on a violin.”

Chef Madonna Broussard, owner of Laura’s Two in Lafayette and a James Beard semifinalist, cooked a multi-course menu featuring Creole Tomatoe Salad, Crawfish Etouffée, Fried Louisiana Catfish with Creole Mustard, and Pecan Carmel Cheesecake with Jean Baptiste Rum Sauce Glaze. We wrap up the evening with a nightcap at The Jesus Bar, in the back of the property, named for its wall-to-wall pictures of Jesus. It all started with one photo hung above the cash register, meant to keep folks honest. Over time, guests began bringing their own portraits of Jesus to add to the collection. Eventually, a visiting Catholic priest gave the place an official blessing. Because here in Acadiana, Catholicism runs deep, nobody around here sees a problem with sipping a cocktail under Jesus’ watchful eye. If anything, it’s just part of the region’s quirky charm.

To step into daily life in old Acadiana, Vermilionville is the place to go. This living history museum and folklife park invites you to walk into the homes and workshops of people living along Bayou Vermilion, a waterway that runs through Lafayette, between 1790 and 1890.

My guide wore a mid-1800s cattle rancher outfit as one of several re-enactors demonstrating crafts and sharing stories about life. “This isn’t one of those museums where you just look at artifacts and read plaques. You’re going to step inside real homes, see history laid out all around you, and maybe even meet folks practicing traditional crafts,” she explains.

That day, I met a weaver spinning brown cotton yarn, part of our Cajun textile heritage. Each home tells the story of a family who lived in it, some filled with tools of the trade, all frozen in time. I imagine my ancestors’ daily lives—their hard-scrabble existence and fierce pride as culture keepers—and I smile with gratitude for the legacy they left me.